Making Tetrahedral Kites

Step By Step—MBK Skewer Tetra!

Very large tetrahedral kites are a pain to build and a pain to set up on the flying field. They're easy but tedious. However, the more pain, the more gain as the sight of a huge complex tetra "nailed to the sky" in a stiff breeze is awesome indeed!

MBK Skewer Tetrahedral (4-cell)

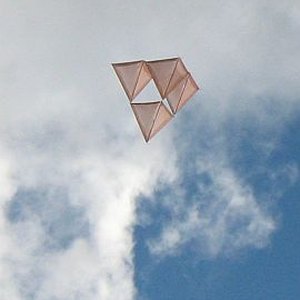

MBK Skewer Tetrahedral (4-cell)If you want to just get started in this direction, without having to take too many pain-killers ;-) a good design to try is the four-cell tetra. See the photo. One of these can be made small enough so it fits neatly inside the trunk (boot) of a modern car, fully ready to fly.

This kite likes gentle-strength winds but is still light enough to be affected by thermals.

If made lightly enough, a four-cell design is just stable enough to fly tailless. But generally, tetras need more cells to become stable over a wide range of wind speeds.

Even our 10-cell bamboo-skewer design benefits from

some added tail. We also have a rather heavy dowel version of

the 10-cell. This kite has plenty of tail but can take a ton of wind. At

the other end of the scale, it won't even stay clear of the ground at

anything less than about 25 kph!

Although time-consuming, constructing tetrahedral kites is fairly easy to understand and carry out.

On this site, there's more kite-making info than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files which provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

Every kite in every MBK series.

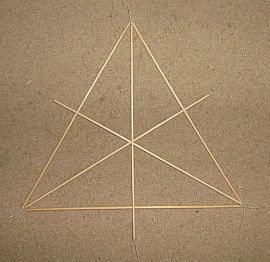

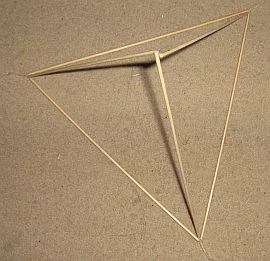

A triangular base of spars comes first. From each corner, another

spar is attached, with all three of these coming together at the top. All

spars are of exactly the same length.

Skewer tetra flying in thermals

Skewer tetra flying in thermalsWhen all four vertices are securely joined, a sail is attached to two sides. Any two sides will do, due to the symmetry of the shape! This whole thing is one cell.

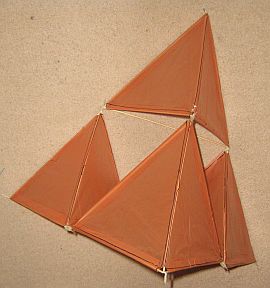

See if you can pick out the four individual cells of my skewer-and-plastic tetra in the photo.

Oh, by the way, don't try flying a single cell—it simply will not be stable. Without a tail, four cells is the minimum!

In general, a four-cell tetra is easily constructed by following these steps:

- Make a single tetrahedral cell as described above.

- Copy it to make three more cells.

- Put three cells on a flat surface in a triangular arrangement so there are three points of contact between them. The sails should all be oriented the same way, and none of them should be lying flat on the flat surface!

- Fasten the cells together at their points of contact.

- Add the remaining cell to the top of the three connected ones, arranging the sail in the same direction as the others and fastening the three points of contact.

Bridle detail

Bridle detailLast, attach a flying line and bridle so the arrangement looks like the photo. Then go out to fly! However, unless the kite is super light, it might need a fair amount of breeze to fly successfully.

A very high proportion of the weight of tetrahedral kites is in the spars. Wait for a windy day, or put your running shoes on and tow it like an exuberant kid!

You might first have to settle on the exact materials and techniques you wish to use.

All sounds a bit hard?Guess what, I'm going to show you the relatively quick and easy way to make a four-cell tetra that loves light-to-moderate winds!

Tetras in Skewers and Plastic

Bamboo BBQ skewers are a great spar material for small tetrahedral kites, being very stiff and strong for their weight.

A cheap sail material is garden-bag plastic. The thinnest, cheapest ones can be used, or you can use thicker brighter-looking plastic for more durability and perhaps better looks!

I decided to whip together a 4-cell tetra just for readers of this page! It uses the cheapest bamboo skewers and garden plastic.

Making a Four-Cell Tetra

Step by Step

Compared to most methods for making tetrahedral kites, the following method is relatively quick and easy:

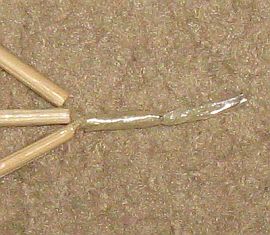

Take a 30 centimeter (12 inch) bamboo BBQ skewer and attach a length of clear sticking tape to one end as in the photo. The tape should be about as long as an average adult middle finger. The skewer is sitting on half the length of the tape.

Carefully roll the skewer in your fingers, attaching the width of the tape to it as you go. Then, keep rolling the skewer while drawing your fingers away from the tip, so the free length of tape spins itself into a tight cord. It should be pretty clear in the photo.

Attach tape to the other end of the skewer in the same way. Then do both ends of another five skewers!

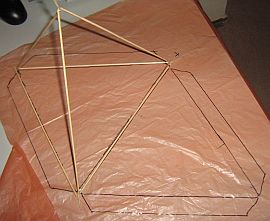

Arrange all six skewers as in the photo and note how the little cords of

rolled-up tape overlap each other at the three corners of the large triangle

of skewers.

Here's a closeup of one of those corners. The three little cords have

been twisted together, then another short length of tape has been

wrapped around the three cords several times. The three skewers are now joined

securely at the tips.

Do the other two corners too!

Finally, draw those three free skewers up away from the floor, and secure the three tips together in the same way as all the others.

(Cue trumpet flourish...) Tada! It's a tetrahedron.

Take your tetrahedron and lay it on a sheet of plastic that you would

like to use as sail material. Trace around the inside of the triangle

that is in contact with the plastic. Use a black permanent marker.

Flip the tetrahedron over, along one side, without letting that side slip or change position. Now trace around the inside of the new triangle that is in contact with the plastic.

Finally, draw tabs in, next to four of the sides of the diamond shape you have drawn. See the photo. I was in a hurry so just eyeballed it—apart from ruling the longest straight lines in with a ruler! Just allow plenty of width to fold each tab over a skewer.

Next, cut all around the tabbed diamond shape with scissors.

The photo also shows a couple of the tabs folded over and stuck down with sticking tape. The tetrahedron has been flipped back to its original position.

Look at that! A complete cell, where the remaining two tabs have been folded over and stuck down.

Now make another three complete cells. Whew. I'll wait here while you create them all...

... finished?

OK, now arrange them as in the photo. All the sails should be facing the same way. At every corner point where the tetrahedrons touch, there should be two short sticks of tape—one coming from each tetrahedron.

Here's a closeup of one join between tetrahedrons. See how the sticking-tape sticks point in opposite directions. Lay them side by side and wrap

more tape around the whole lot, using several wraps to make it

strong.

Take a length of 20-pound flying line, about 2 skewer-lengths long,

and attach it to the kite as shown in the photo. I just used Half Hitches around the sticking tape at both points. Small tetrahedral kites such as this one do not require more than 20-pound line.

Also tie a small Loop knot into the bridle, so the line angles are approximately as shown. The exact position is not as critical as for other types of kites. It should fly fine!

Here's the Skewer Tetrahedral kite in flight:

Tetrahedral Kites From Straws

Yes, that's ordinary drinking straws, in either paper or plastic. Now that you know all about the details of construction, you should also be able to whip up a four-cell tetra using straws instead.

One quite popular method is to feed a line through each of the six straws, leaving an ample amount hanging out each end of the straw. A simple three-strand knot at each vertex keeps the whole structure rigid. Well, it's rigid enough for the purpose. The extra lengths of line at each vertex can be used to tie the vertices of several completed cells together.

Here's some ideas for those threaded lines:

- polyester sewing thread

- embroidery cotton

- light fishing line—could be fiddly!

- any type of 20-pound kite line

With use, the line can tend to cut into the ends of the straws and shorten the life of the kite.

One proven idea for plastic straws is to carefully melt each end of each straw, by touching it to a hot plate. Do this just enough to soften and thicken the wall of the straw a little, right on the end!

For paper straws, you could try a single wrap of narrow sticking tape around each end of each straw for reinforcement. This would also increase the weight of the kite a little, but it's worth a try.

Regarding sail materials for tetrahedral kites, there are many options:

- wrapping paper

- ripstop nylon (spinnaker cloth)

- rice paper

- Mylar

- cellophane

- plastic bags

- builders' drop-sheet plastic

Tetrahedral Kites—General Points

One thing to try, if you have the patience, is to connect four 4-cell tetrahedral kites together to form a 16-cell! It will fly more stable than the 4-cell so should have a better wind range.

Out in the Field

Box-kite stories of my real-life flying experiences are worth checking out!

They're illustrated with photos and videos, of course.

This page hardly scratches the surface of this fascinating corner of the kiting world. Tetras can be tied together in an infinite variety of configurations, requiring complex bridles to match.

More durable tetras can be constructed from fiberglass or graphite spars and covered with ripstop nylon sails like most retail kites. With sufficient spar thickness and stiffness, these kites don't need the full six-stick tetrahedal-cell construction. Instead, other forms of bracing can be used that use far less spar material.

Making tetrahedral kites is an area that remains wide open to experimentation and new ideas! Perhaps you might end up inventing your own method, as I did, with .... skewers and plastic. In fact, a couple of my smaller box-kite designs use bamboo skewers.

As mentioned earlier, there's more kite making on this site than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files that provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

That's every kite in every MBK series.