- Home Page

- Kiting Knots

Knot-Tying Instructions

Kiting Knots Used in MBK Designs

There are knot-tying instructions here for any stage during the

construction of an MBK kite.

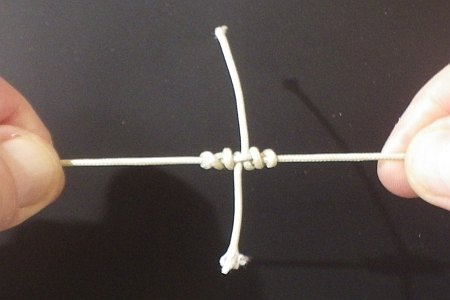

Blood knot

Blood knotYou can make do with just a few simple knots to begin with, but eventually you will discover the convenience and satisfaction of using all the right ones!

The bigger the kite, the more important it is to use the right knots. Often this relates to strength, since safety margins can be slimmer with bigger, stronger-pulling kites.

All of these knots have been used in the MBK kites, particularly the large Dowel and Multi-Dowel Series designs.

The Blood knot is a beauty; no other knot I've tested preserves the line strength better than this one!

My Kiting-Knot Collection

There's a separate page for each knot, or class of knot, since I have added a few comments on their usage. Talking about usage, our MBK kites have logged quite a few hours over the years!

For beginners, here is a kite parts glossary. It's handy in case you come across an unfamiliar term or two in these descriptions and illustrations.

Line-Mending Knots

Loop Knots

Other Useful Knots

These instructions have been long overdue. I used to get comments like "The kite making instructions are great, but I have trouble with the knots."

It was time to fix this problem for good! Of course, some of the simplest knots are just here for the sake of completeness. Yeah, I can be a touch academic at times.

Hopefully, my approach of using multiple closeup photos in each knot-tying illustration has made them easy to follow.

There's no completely standard naming system for knots. However, I hope the names used here prove to be both simple and descriptive!

I hope you found these knot-tying instructions useful.

One last thing—see my knot-strength page if you are curious about how various knots can weaken your flying line. Yep, we are all flying on line that is considerably weaker than the advertised breaking strain. :-| At least at the bridle end, some sort of knot is always required!

Wind-Speed Handy Reference

Light Air

1-5 kph

1-3 mph

1-3 knts

Beaufort 1

Light breeze

6–11 kph

4–7 mph

4–6 knts

Beaufort 2

Gentle ...

12–19 kph

8–12 mph

7–10 knts

Beaufort 3

Moderate ...

20–28 kph

13–18 mph

11–16 knts

Beaufort 4

Fresh ...

29–38 kph

19–24 mph

17–21 knts

Beaufort 5

Strong ...

39–49 kph

25–31 mph

22–27 knts

Beaufort 6

High Wind

50-61 kph

32-38 mph

28-33 knts

Beaufort 7

Gale

62-74 kph

39-46 mph

34-40 knts

Beaufort 8

Some Rather Vague Knot History

The Simple knot, and its multi-strand variants, is so simple that it is impossible to know for sure when it was first done, by whom, or for what purpose! Agree? Heck, a chimp could do one eventually, by fiddling around with a short length of rope.

The Granny knot is also known by such names as the Booby knot or Lubbers knot. These terms have a not-so-complimentary feel, don't they! It seems that sailors and other knot experts :-) look down upon this knot. It probably doesn't appear in too many nautical manuals of knot-tying instructions. That's for good reason, it turns out.

The Granny is not a safe way to attach two ropes together, for example. However, it does have its uses in kiting, and you can always apply a small drop of glue to fix such a knot permanently.

By the way, this is also a very old knot, with some examples in museums that are thousands of years old. It goes back a lot further than grannies in the 1940s or 50s!

The Loop knot and its variations seem to have a nautical origin. Various kinds of loop knots come from European countries like Spain and France, both of which once had great numbers of sailing ships on the sea. They were for military, trade, and fishing purposes.

Even ancient Egyptian ships have been found with intact loop knots in the rigging. These were quite similar to the modern Bowline loop knot!

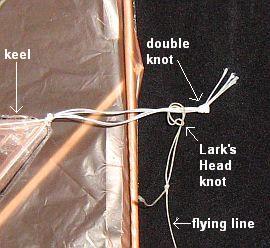

The Lark's Head knot is also known as the Cow Hitch, not to mention about a dozen other names! This knot first appeared in manuscripts in the first century and has been used extensively on land and sea ever since.

I find it's a bit tricky to undo a Lark's Head when it's used on 20-pound Dacron line, but this gets much easier as the line weight goes up. It's a piece of cake with 200-pound Dacron!

The Prusik knot is definitely a climbers' knot, since it can be traced back to its Austrian inventor and keen mountaineer, Dr. Karl Prusik. That was back in 1931. Dr. Prusik also authored a book of knot-tying instructions for mountaineering.

I use this knot extensively in the bridles of most of my kites, in both the Skewer and Dowel Series. No set of knot-tying instructions for kites would be complete without it. Unlock, shift it along a bit, lock it again—works great!