- Home Page

- Popular Kites

- Sode Kite

The Sode Kite

Some Background

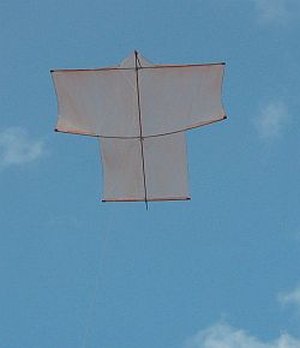

The sode kite, or sode dako as it's known in Japan, is also known as the kimono kite. "Sode" actually means "sleeve of a kimono."

MBK Dowel Sode

MBK Dowel SodeThe form of one of these kites looks similar to a Japanese kimono stretched out flat. Traditionally, this kite was built and flown to ensure the health and happiness of a newborn boy.

As far as I know, plenty of traditional sodes still fly in Japan, along with a number of Western versions that are now available in shops.

Like Chinese kites, most Japanese kites are works of art where a lot of effort is put into the decoration of the sail.

Centuries ago, it was common for a string "hummer" to be strung

tightly across near the leading edge of the kite. When in the

air, the string would make a humming noise in the breeze. This idea was

borrowed from even earlier Chinese kites.

The sode kite is a good light-wind flier but often needs a tail to cope with fresh winds. Interestingly, many Japanese believe that a kite that needs a tail is poorly designed or built. It's true that most traditional Japanese kites fly without tails. Although the kimono-kite design isn't exactly popular in the West, a few notable kite-makers have made them. In large sizes and with the latest materials and modern decor, these kites do make a good impression on spectators!

Some Western versions also stay true to an artistic ideal, with long hours of intricate sail work undertaken by the kite maker. The results are usually very different to the Japanese designs, though! For example, look at that patchwork design, further down, by Dr. Kai Griebenow.

On this site, there's more kite-making info than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files which provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

Every kite in every MBK series.

The frame of a sode kite looks pretty much the same regardless of the overall size. The thickness and strength of the spars are just scaled up or down depending on how big the kite is. Although the Japanese are known for flying very large kites, I haven't heard of any huge sodes being flown. However, some makers do go the other way and make some very tiny sode kites! These and other variations are listed and discussed a bit further, below:

Geometric artistry

Geometric artistry- The overall size of both traditional and modern Western sode-inspired kites varies a lot.

- The basic outline hardly varies at all, and if it's quite different, is it really a sode?

- Traditional construction materials hardly vary at all from kite to kite, which contrasts with the variety of modern kite-making materials.

- An accurately made kimono kite can fly without a tail in light winds and a tail lets it fly in stronger winds.

- Traditional kimono kites are decorated with many different designs and the few shop-bought versions are also available in colorful designs.

- The number of bridle legs varies according to the size of the kite.

- Traditionally, the sail was hand-made paper, but these days nylon, mylar, or polyester is commonly used.

Here are a few comments on each of the above points:

Size. I've seen plans and write-ups for sode kites around 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. There's even a commercially available design by the (late) famous kite-maker Reza Ragheb that measures 3.8 meters (9 1/2 feet) in length. However, the traditional variety that are still flown in Japan are generally much smaller than this. At the other end of the scale, a Japanese kite maker managed to take out the Worlds Smallest Kite Competition in 1998 with a very tiny sode design. His name was Hiko Yoshizumi, and his delicate little creation measured just 10 by 8 millimeters (4/10 by 3/10 inch)! To qualify, it had to fly at a better than 10-degree line angle.

Shape. Sode kites all look pretty much the same in outline, although the triangular tip at the nose end can vary in shape and size. Also, the left and right edges of the top and/or bottom regions of the sail are not always perfectly straight up and down as in the traditional design. These variations are just for artistic reasons. For example, the Nosey kite by Charlie Charlton has some curves and tapering in its sail outline.

Construction. The Japanese like to refer to the kite frame as the "bones," and the sail material as the "skin." Straight slivers of bamboo are used for the single longeron, two upper spars, and the shorter lower spar. The lower spar can be bent in the middle or bowed a little. This gives some side area toward the rear of the kite and helps with directional stability. In other words, the kite will fly without a tail in a wider range of wind speeds. Some modern sodes have pockets in the sail into which the ends of the spars are inserted. Hence they are collapsible for easy transport, just like many modern diamonds or other flat kites.

Tails. I suspect that typical tails for these kites are fairly simple, since most of the time the idea is to not use them at all. Not being an expert on Japanese kites, I'm not sure what traditional Japanese kite tails are like. Long streamers of tissue would work. Come to think of it, I have seen illustrations where some rectangular Japanese kites have two simple streamer tails.

Decoration. First, here are some modern methods. Strips of different-colored material can be joined together before the outline is cut. The appliqué technique involves sticking light but colorful cutout patterns onto the sail material. Printed sail material can be used. I've even come across a guy who prints out sails for his sode kites on an ink-jet printer! Hand painting or airbrushing can be applied after the kite is constructed. There's a bunch of different ways to decorate a kite. Nearly all traditional Japanese kites were brush painted with bright-colored natural dyes and black ink. This would have included the sode or kimono kites as well.

Bridle. When it comes to bridles, they do vary quite a bit on sode kites. The smallest kites just require two bridle attachment points, where the upper cross-spars join to the longeron. My MBK Skewer Sode is like this. The largest kites fly well on six bridle legs, where there is a bridle point on either side of both central bridle points. That is, there are three points on each of the two main cross-spars. For medium-sized kites, just the four outer bridle points are sometimes used. Finally, for strong wind flying, an extra bridle point where the bottom spar crosses the longeron is sometimes required to prevent the longeron bending excessively under the strain.

Sail. Traditionally, sodes used washi paper that was hand made. These days, ripstop or spinnaker nylon is a common choice for the larger kites. Smaller kites made in workshops might still use plastic or tissue paper.

Like to see a video clip? Just scroll down to near the end of this page.

Sode Kites in Action

You'll have a much harder time spotting a sode kite than seeing, say, a diamond or a delta in the air. There are some examples of this type of kite in the shops, but mostly, it seems they are made by kite makers looking for something different.

Out in the Field

Sode-kite stories of my real-life flying experiences are worth checking out!

Illustrated with photos and videos, of course.

Also, with two big rectangular areas of sail, these kites are perfect for doing something really artistic!

Some very well-known kite makers have chosen this style of kite to exhibit their talent for creating flying works of art. For example, there are Janneke Groen from the Netherlands and the late Reza Ragheb.

When designing for looks, the bigger the kite, the bigger the impression on spectators! That might explain why some of these designer kites are so large.

Some Sode Kite History

At this point, I haven't yet waded through any big books on Japanese kite history, so I haven't got anything specifically on the sode kite. However, there are some general points that would apply to the sode design.

Most artistic Japanese kites were developed in the Edo period from 1603 to 1867. At this time, Japan was closed to foreigners. Different designs originated from different regions of the country, including, presumably, the sode dako.

The early sode kites would have

been decorated with scenes from Japanese folklore or mythology. Bright

geometric patterns were sometimes used too, which makes you wonder

whether some of those early designs would not look out of place today,

hanging in the local kite shop.

The video shows our own homemade MBK Dowel Sode in flight.

As mentioned earlier, there's more kite making on this site than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files that provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

That's every kite in every MBK series.