Building Box Kites

Two Unconventional Approaches

Perhaps you haven't thought about it much, but building box kites successfully does not necessarily mean using two sets of cross sticks to tension the sail! That time-honored technique is very good design for a couple of reasons.

MBK 1-Skewer Box

MBK 1-Skewer BoxIt is relatively simple. Also, it minimizes the total weight of the kite, for any given combination of spar and sail material. Light kites are good kites, for any proven configuration.

But if you really want your box kite to be a little different, why not try one of the two methods outlined below. It so happens that both of these approaches will result in a slightly heavier kite for its size than a traditional approach would generate.

However, what does that matter in ... "box kite weather"? That is, a good stiff breeze! You will still end up with a perfectly airworthy kite for those windier days. Or maybe it'll be for when a solid trade wind is coming off the ocean.

I would recommend a slightly larger gap between the upper and lower cells of the kite than the distance from the leading edge to the trailing edge of each sail panel. This is for the sake of stability.

Let's get back to that "two sets of cross sticks" idea for a moment...

I have actually managed to go one step further with my 1-Skewer Box design. There is only one pair of cross sticks, with a strategically placed internal tensioning line keeping the kite rigid. There it is, in the closeup inflight photo.

On this site, there's more kite-making info than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files which provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

Every kite in every MBK series.

Building Box Kites Unbraced

Unbraced with cross sticks perhaps, but it's still rigid. A visitor to this site submitted this idea, with photos, and has proven the concept in stiff winds. Thanks Jack!

Note that, unlike my MBK designs, this idea works best with square section dowel rather than round.

The first photo down there shows the kite frame, around which the upper and lower cells are wrapped. This contrasts with the more conventional approach of attaching the spars to the sail material first, closing the cells, and then applying tension by inserting cross sticks. Both approaches work well for those who prefer them!

Notice the four short sticks near each end of the frame and how they are secured with small accurately-cut wood blocks. The second photo gives a closeup view of such a block. Obviously, you need a woodworking aid such as a table saw to do this quickly and accurately. But if you can organize that, it's a solid approach to building box kites.

Complete frame

Complete frame Closeup of corner block

Closeup of corner blockHere are a couple of further points...

As with building box kites the conventional way, the short pieces should be positioned to the center of the cells, along the main spars. (Yes, I know my Moderate Wind Dowel design has its cross sticks near the trailing edges. In lighter winds you can get away with that.)

Apparently, a press-fit can work if everything is cut accurately enough. I would prefer to glue all those joins, though, since the kite will be flying in strong wind. The frame will be under considerable stress.

Building Box Kites With Slab Panels

You have to choose slabs with reasonable lightness and strength, of course.

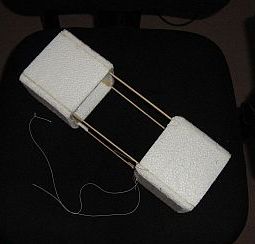

I explored this idea some years ago using bamboo skewers for spars. Small slabs of packing foam can be glued together to form the upper and lower cells before gluing the skewers into the inside corners. At this size, the kite was rather inefficient and heavy. But it flew!

Experimental foam slab Box

Experimental foam slab BoxThe nice thing about thick slabs of foam is that they lend themselves to shaping. I carved the edges of the slabs to create a crude airfoil section like a plane's wing.

This gave it more lifting force, and I'm sure it contributed to the successful flight in the gusty fresh wind down at the park. Actually, it was more like gale force near the end of the flying session!

There's the kite, in the photo.

The foam slabs were so solid that the skewer tips didn't need to go all the way to the nose and tail of the kite. Ordinary woodworking glue was used to secure the bamboo to the foam. The foam slabs were just butt-joined to each other and secured with the same wood glue. The dimensions were arranged so the whole thing was square and hence could fly on one edge like a traditional box design.

Foam slabs would lend themselves to building box kites with rectangular cells rather than square. You would then need to fly the kite flat rather than on one edge. This would require a four-leg bridle.

OK, I hear you say "we don't often get gale-force winds around here." Not to worry—just build something bigger and look around for foam slabs that are relatively thin compared to their other dimensions. Use wood dowel for the spars.

For the best chance of success, I would go for dowel and slabs that appear a bit thin or weak for the job. If anything breaks in flight, just try again with a slightly stronger design (see below). Otherwise, it's just too easy to build something that won't fly in anything but a gale or category 5 storm due to sheer weight. ;-)

In the case of foam slabs breaking, that would mean trimming down the dimensions a little to achieve greater stiffness—leaving the thickness the same, of course.

As for busted dowels, just buy the next size up that is available and try again.

Worried about the "airfoil shaping" idea for the foam slabs? It's not strictly necessary, but it would still be helpful to at least round off the leading and trailing edges of both cells. This will definitely cut down the drag forces a little and hence help the kite to be more efficient.

And how about building box kites with balsa wood panels? In theory, balsa wood could be used in a similar way to the foam-slabs idea.

Do you have any aeromodelling skills? Have a go at making a

little balsa box kite; it should work fine, particularly if you carve a

bit of an airfoil section into the sails! More than just decreasing

drag, this would also increase the lifting force of the sails.

Try this using thick slabs of the lightest balsa to get some rigidity. Perhaps try a harder grade of balsa for the main spars. This way, they can be thinner and hence have lower drag to increase the efficiency of the kite.

Balsa wood would be ideal for building box kites in tiny sizes. Ones that would use ordinary sewing thread for flying line, perhaps! Also, these days it's easy to get hold of polyester sewing thread in supermarkets. That's similar to Dacron, the single-line-kite flier's favorite.

Some Simple Bridle Ideas

Regarding the towing point, this should be located on one spar, about midway along the upper cell. A simple two-celled box kite of almost any size seems to only require this single attachment point in order to fly stable. Perhaps a tail would be required in the case of very small box kites.

Some experimentation will be required to get your box kite trimmed for best performance. Try this approach:

- Attach a bridle loop between the nose and another point at least halfway along the same spar.

- Attach the flying line to this loop with a sliding knot.

- Start with the knot almost level with the leading edge of the upper cell and shift it back in small steps until the kite gets best height.

Why not try some of these ideas for building box kites. Don't let those windy days go to waste!

As mentioned earlier, there's more kite making on this site than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files that provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

That's every kite in every MBK series.